Wiki article

Compare versions Edit![]()

by Hubertus Hofkirchner -- Vienna, 06 Jan 2019

Imagine you want to buy a calculator. They show you a model with a lot of fancy electronics. You test it. You enter 100 / 2 and tap CALCULATE: 68. Repeat: 100 / 2 = 62. You try it again: 70. Would you buy it?

There was this CEO. His company prepared an international expansion, all by the books. They contracted an agency to do a demand forecasting questionnaire, asking local consumers if they would buy the company's product. A large factory was built to serve the forecasted demand, at an investment of several hundred million dollars. However, now actual demand turns out to be much lower. Low capacity utilisation and inefficient production costs cause painfully accumulating losses.

Should our CEO shut down the factory to avoid further losses? Well, a rational decision would need him to buy another demand forecast, doesn't it? He is back to square one.

The issue of 68

There is a virtually unknown huge problem with demand forecasting by questionnaire survey.

For example, when asking people if a coin toss will show heads or tails, you'd think that a survey will result in the answer 100 / 2 = 50, giving each side a 50 percent chance.

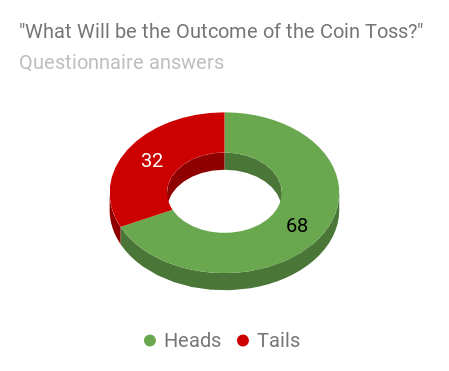

Not so. In reality, 68 out of 100 people tick heads and 32 tick tails, on average, give or take a few percent. (Feel free to replicate this little experiment in your own next questionnaire.) 68 percent heads suggests a very strange coin indeed, where heads is more than twice as likely as tails – if you believe that surveys for future questions are accurate.

Never trust questionnaires for future questions

At Prediki, we obviously do not believe such a thing. We know that surveys for future questions (“What will be?”) will give you heavily distorted results for pretty much any future question. The distortions become enormous when asking for future human action.

How come? In the coin toss case, the so-called order bias distorts people’s answers. Worst of all, most people – like our CEO of above – buy easily into questionnaire surveys. They sound authoritative: “68 percent of respondents expect heads.” Even more so with experts: "90% of dentists recommend toothpaste XYZ." This type of statement may be useful for marketing communications but clearly not for responsible executive decision making.

There are several dozens of such distortions. For example, overclaim for behavioural intentions can be easily off by a factor of four or even more, due to the social desirability bias. We humans always believe ourselves to behave better than we really do. Overclaim for purchase intent questions can be in the same order of magnitude of up to five times, always with a wide range of error, due to the acquiescence bias as respondents try to please the interviewer.

The solution: Ask for bets

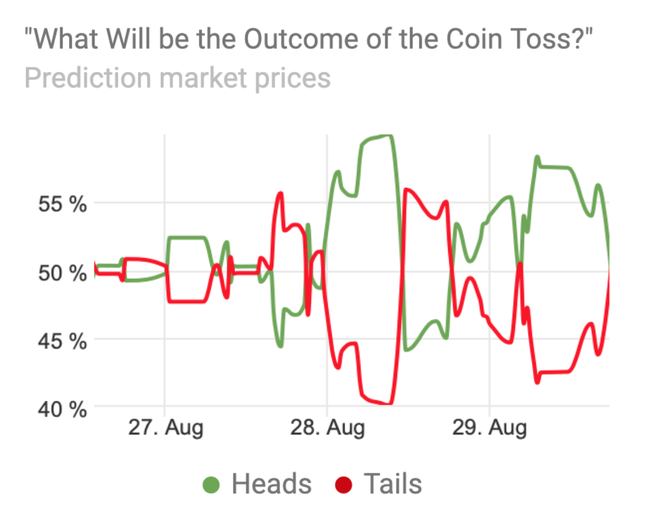

To overcome these biases, we must ask people not for answers but for bets. When respondents trade the possible results of the coin toss on our prediction market platform, the average of individual bets is a 50% likelihood for heads and 50% for tails. Now that looks more like a coin.

Now, you may say, that’s an easy exercise. But experiments devised by Prof. Charles Plott of the California Institute of Technology have generated ample evidence that people participating in a market mechanism can “solve” very complex formulae. People can anticipate the future accurately in a dynamic process of sequential adjustments, aggregating fragments of private knowledge distributed over different individuals.

The experiment went as follows: 90 participants had to invest into ten “possible futures”. Which was most likely to occur? They were given three pieces of “information”, an indication that one of three futures may occur. There was a one in four chance that the correct future was in their information set, while the other nine possible futures occurred in their information set with the chance of one in twelve (3/4/9=1/12).

Astoundingly, Plott's prediction market singled out the correct future in no less than seven out of eight repeat experiments. Even in the eighth market, the correct future came second out of ten. Plott subsequently went on to perform similar experiments to predict future sales of HP’s printer division. Famously, his (first generation) market mechanism significantly beat internal HP forecasts. Modern second-generation prediction markets with their inbuilt qualitative extensions have even higher accuracy, in addition they spell out the major factors driving the forecasts and identify potential problems which need fixing to maximise sales.

Let's hope that someone at the above-mentioned CEO's company reads our blog and points him to a better method of demand forecasting.