Wiki article

Compare versions Edit![]()

by Hubertus Hofkirchner -- Vienna, 16 Jan 2019

Shrinkflation, downsizing packaged products without changing their price, is a common practice in consumer goods companies. Quite a few do it, so it must be a good marketing tactic. Or is it? Are consumers really too stupid to notice?

Cadbury, a Mondelez company, recently shrank their chocolate bar without reducing its price commensurately, hoping that consumers would be nice and keep buying their “creamy chocolate”. The tactic backfired: “Cadbury creamed by customers” read a typical headline after the downsizing. Consumers were outraged, a veritable shitstorm broke in traditional and social media: “Social Media slams Cadbury”.

It is not the first time that Mondelez ran into this kind of trouble. Already in 2016, they shrank their Toblerone chocolate bar by spacing out the chocolate’s distinctive peaks, lowering its weight but keeping the pack volume. Did the supposedly stupid consumers “Mind the Gap”? Very much so. People said that it was rather the erstwhile iconic chocolate bar which now looked stupid.

Why shrinkflate?

When confronted, shrinkers typically blame rising ingredient cost. More creative excuses refer to the fashionable topic of the year, such as the Financial Crisis, Brexit, Global Warming or President Trump. While such defensiveness does not explain their choice of product shrinking over a straight price increase, it suggests that something may be not quite right: shrinkflation smells of sneakiness and dishonesty.

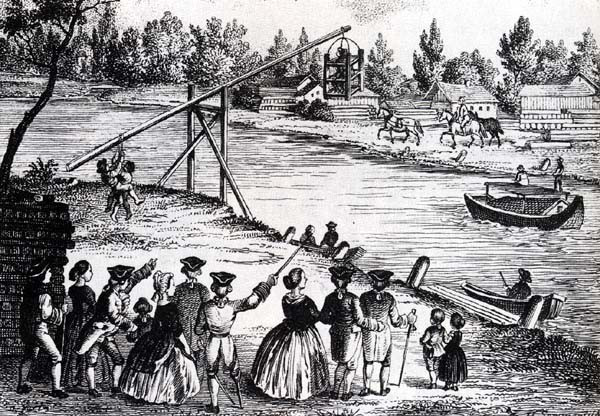

In fact, bakers who sold underweight bread loaves were punishable by baker ducking (“Bäckerschupfen”) in Vienna until as recently as 1773. The offending baker was tied to an oaken stool attached to a long beam and dunked into the river Danube, to the enjoyment of the Viennese citizenry.

Admittedly, the Middle Ages and its entertainment options were a bit backwards. For an up-to-the-minute opinion on shrinkflation in the times of Netflix, I ask Melissa H., a fund manager with Raiffeisen Capital. “Is this when suddenly there are only three bowls of soup in a packet instead of four?” she asks. “I absolutely HATE it.” Ok, she's also my wife and does most of the shopping. For a dutiful husband a sample of n=1 is all he needs but let us take a closer look.

Scientific arguments

How could this deceptive tactic become so widespread? After all, packaged goods must state their content weight or volume nowadays, by law. More than 2,500 products shrunk in the UK between 2012 and 2017, according to the UK's National Statistics office.

(1) Many producers practice it, so it must be a good tactic. Therefore more producers will adopt it, so it must be a good tactic. This circular logic summarises the first key argument in one of the few scientific papers on package downsizing (Gourville Koehler 2004).

(2) Another argument is that shoppers may be less sensitive to a lower volume than to a higher price. In a study for the above mentioned academic paper, the vast majority respondents preferred ½ pound of coffee beans for $6 to one pound for $12. The authors interpreted this result to support their suspected irrationality, as respondents should have been indifferent. However, the result could just as well be explained by buyers’ quite rational expectation of a volume discount. Occam’s razor, anybody?

(3) Intending to nail their point, the authors finally performed a regression analysis of real-world price changes vs. volume changes for a certain product range. The exercise also seemed consistent with said consumer irrationality: sales correlated more with price changes than with volume changes. However, the authors admitted that they did not factor in promotional activity which accompanied price reductions. Obviously, promotion enlarges the effect of a price reduction more than a clandestine shrinkage. Beware of inductions from incomplete data.

It is a well known fact that surprising science results increase the chances of publication in a scientific journal, and that experimental replications fail to reproduce the original “surprises” quite often. Prediction markets can even predict the fakes, and most were found in psychology and marketing journals.

A methodic fallacy?

Here's a very different explanation for the fashionable shrinking: We can assume that Mondelez, Cadbury, and Toblerone marketers probably instigated some market research exercise before implementing the rather onerous changes to packaging and even product. Could corporate shrinkflation activity only be an artefact of using flawed research methods?

In the next instalment, we will first look at some strange results of direct questions about pack size and price relations when fielded with a traditional questionnaire, where consumers can simply claim what they will buy. Then we will look at the answers when using a behavioural method where answers will be verified and respondents are rewarded for accuracy.

You will learn how to optimise size and price safely and avoid future media disasters to boot.

Follow the author to stay tuned for next week’s article.